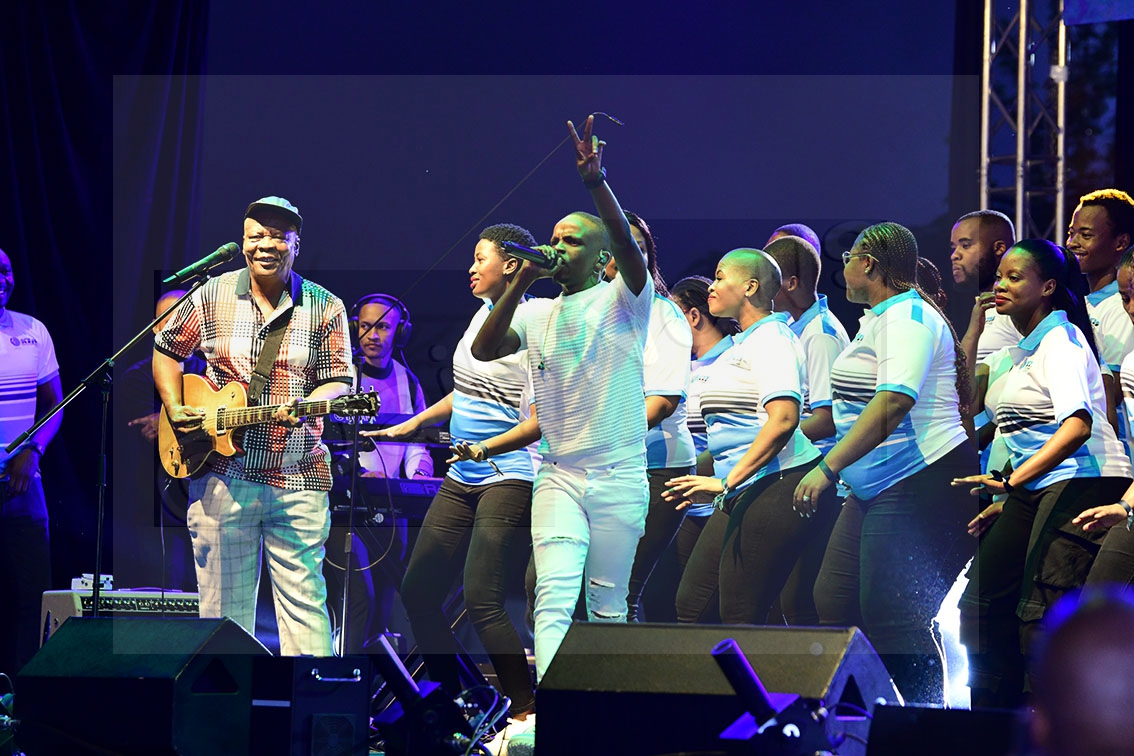

Gwangwa bows out leaves mark

26 Jan 2021

Akin to the Biblical David playing the harp to assuage evil spirits tormenting King Saul, the music of Jonas Gwangwa gave hope and temporary relief to an oppressed South African majority during the apartheid era.

Gwangwa, who passed away at the weekend aged 83 from COVID-19 related complications, rose to fame as a jazz musician in South Africa, and while exiled to the United States and later Botswana, used his art to alert the world of apartheid segregation.

During his time in Botswana, Gwangwa founded the band Shakawe, composed of fellow South African musicians, tenor saxophonist Steve Dyer, Dennis Mpale, Tony Cedras and various Batswana musicians, including the late scribe cum musician Rampholo Molefhe.

In his popular tune, Batsumi, Gwangwa adapted lyrics from legendary local guitarist George Swabi’s classic Tswana folk tune Bagammangwato.

The lines Batsumi bale tsomelang metlhabeng/Leseke la bolaya bommatsale/Ba basetlha batshwana le dikgokong were given new life by Gwangwa, who added his own jazzy melody to create the masterpiece.

“I introduced those lyrics to him when we performed as Shakawe,” the Serowe-born guitarist Bonjo Keipedile tells BOPA, “and Gwangwa later recorded it to his own melody.”

Keipedile recalls Gwangwa as a kind-hearted gentleman who genuinely cared about others and always considered the interests of the Batswana musicians he worked with.

“The band was initially composed of Dyer, the South African who had come from Durban, and two Batswana, Gabriel Selato and Tsholofelo Giddie. I then joined them; other locals Molefhe, Whyte Kgopo and Japie Phiri came later. Gwangwa came up with the name Shakawe, naming the band after the Botswana village in the Okavango,” Keipedile said.

Apart from allowing Botswana musicians to develop their art in live performances, Gwangwa also made attempts to organise scholarships for them to study abroad, Keipedile said.

His passing, thus, is a major loss of a friend of the local music industry.

Born Jonas Mosa Gwangwa on 19 October 1937 in Orlando East, one of the oldest townships to the South West of Johannesburg collectively known as Soweto (an acronym for ‘South Western Townships’), he was drawn into music at an early age.

A young Gwangwa was handed a trombone by Father Trevor Huddleston, an Anglican clergyman who in the 1950s was priest in charge of the parishes of Sophiatown and Orlando, who also gave a 14-year-old Hugh Masekela his first trumpet.

The youngsters founded the Huddleston Jazz Band and taking a cue from African American jazz great Dizzie Gillipsie, Gwangwa started wearing a black beret on stage; something that would be a lifelong trademark.

Soon after, the Jazz Epistles were born, a seminal jazz band of Sophiatown-era Johannesburg, with Abdullah ‘Dollar Brand’ Ibrahim on piano, Morolong Kippie Moeketsi on alto saxophone, Gwangwa on trombone, Masekela on trumpet, Jonny Gertze on bass and Makhanya Ntshoko on drums.

In 1961, Gwangwa then left South Africa to tour Europe with Todd Matshikiza’s King Kong musical, beginning a three-decade period in exile. Gwangwa worked on the musical arrangements of Harry Belafonte and Miriam Makeba’s 1965 Grammy Award winning album An evening with Belafonte/Makeba.

With Masekela also having an American billboard chart topping number one hit with Grazing in the Grass in 1968, South Africa’s exiled musicians were gaining international popularity.

In the 1970s, boyhood friends Gwangwa, Masekela and Caiphus Semenya recorded an album together as the Union of South Africa, and on the album Gwangwa was the sole composer of the hit jazz standard Shebeen.

While touring Botswana in 1976 with Caiphus Semenya and Letta Mbulu, Gwangwa got to reunite with the love of his life, Violet Molebatsi Kabe, a childhood friend from Orlando East whom he soon married, and they chose to settle in Gaborone.

1978 saw the formation of MEDU Art Ensemble pioneered by South African exiles Thami Mnyele, Mongane Wally Serote, Keorapetse Kgosietsile, Baleka Mbeta, Mandla Langa, British journalist Gwen Ansell and Motswana art curator Phillip Segola.

MEDU spread the anti-apartheid message through seven semi-autonomous units - film, graphics, music, photography, poetry, publishing and research as well as theatre.

“Shakawe was the musical wing of MEDU, the ensemble organised instruments for us, and we collectively used different art forms to sensitise people on the struggle against apartheid,” Keipedile says.

In his tribute published online on Sunday, former South African President Thabo Mbeki wrote that, “in addition to being an effective instrument in advancing the struggle against apartheid, MEDU played a pivotal role in strengthening ties between the exiled South Africans and their Botswana hosts.”

Masekela followed Gwangwa to Gaborone and founded his own backing band Kalahari, which included South African female vocalists Nomasonto ‘Sonti’ Mndebele, Mandisa Dlanga and Stella Khumalo, vocalist Tshepo Tshola from Lesotho and Botswana musicians, guitarists John Selolwane and Banjo Mosele as well as drummer Mopati “Bullie” Tsienyane.

Masekela set up the Woodpecker studio at Notwane to the south of Gaborone where he recorded his 1984 album Techno-Bush, and from where his Kalahari and Gwangwa’s Shakawe bands engaged in jamming sessions.

On June 14 1985, the apartheid South African Defence Force (SADF) launched the cross border Gaborone raid targeting anti-apartheid activists, killing MEDU visual artist Mnyele, treasurer, Mike Hamlyn and also bombing a house recently vacated by MEDU leader Tim Williams.

“The raid destroyed everything,” Keipedile says. “Gwangwa was forced back into overseas exile in London then the United States at a period he had been making major plans for us, the Shakawe collective.”

Realising that cultural activists were being targeted by the apartheid regime, both Masekela and Gwangwa returned to overseas exile, and this put paid to this brief period of Gaborone being a regional cultural hub of sorts.

Gwangwa focused his attention on the Amandla Ensemble, through which he had been tasked by the ANC leader in exile Oliver Tambo, to sensitise the world on the plight of oppressed South Africans.

Directed by Gwangwa and performed by exiles that had been organised in Angola, Amandla the musical was a story of the struggle for liberation carried in a musical form, and performed in over 40 countries worldwide.

Gwangwa earned an Oscar nomination for composing the score for the 1987 Hollywood anti-apartheid film Cry Freedom, and in 1991 returned to South Africa to continue his music in a post-apartheid democratic society.

Known for hits such as Kgomo, Morwa, Batsumi, Diphororo and others, he will be remembered for his music, intrinsically linked with cultural identity and the struggle for human emancipation.

In an eerie coincidence, Gwangwa passed away on January 23 2021, the exact same date of the passing on in recent years of contemporaries Masekela in 2018 and Oliver Mtukudzi in 2019.

Gwangwa recently lost his wife Violet, who died just 17 days before her husband, and they leave behind four sons and three daughters. ENDs

Source : BOPA

Author : Pako Lebanna

Location : GABORONE

Event : Obituary

Date : 26 Jan 2021